Tennis, In Need Of A Saviour?

Last week Patrick Mouratoglou, the occasionally controversial coach of Serena Williams, made some rather bold claims about the state of tennis while promoting his new ‘Ultimate Tennis Showdown’ tournament:

Mouratoglou: “Ten years ago the average age of the tennis fan was 51 years old. Today it’s 61. In ten years it’s going to be 71… Tennis is not able to renew its fanbase… The world has evolved in the last 10-20 years but tennis has never changed. Tennis is in trouble, I want tennis to survive.”

A misquoting of one part of that stat and a misunderstanding of average slopes aside, I’m fairly certain Mouratoglou was just being intentionally incendiary. Proclaiming the average age of tennis fans to be ‘61’ is almost certainly silly (even sillier to imply the average age of a tennis fan in 40 years time will be 101), with that particular figure being plucked from a narrow study of broadcast and cable television ratings in the United States only. The study not only ignores every other country’s consumption habits, but also doesn’t include digital/streaming (read: young) viewership. Neither does it factor in on-the-ground tournament attendee demographics, whose avg age seems to actually be dropping in North America and has always been much lower in some of tennis’ faster growing markets like China (for e.g 70% of fans were under the age of 40 at the 2018 Beijing Open). Anecdotally, the events I’ve been to, including European ones, also seem to have a pretty even spread of ages, and certainly no shortage of GenZ & Millennials.

As a result, ‘61’ is a fairly unusable figure when trying to come up with an accurate estimate of the real avg age of a tennis fan. Americans who watch linear TV, unfortunately for them, aren’t really getting younger. So it’s not particularly surprising that that specific metric would be stable or higher than it was 10 years ago.

Tennis twitter, the eccentric corner of keen tennis fandom, wasn’t pleased with the doomsaying. I’m guessing Mouratoglou’s comments would have been more palatable for the hardcore tennis community had his choice of words not made some fans feel like both they, and the sport, were about to be ungratefully carted off in a hearse, rolling towards the nearest cemetery for extinct luddite sports, as mad-scientist Mouratoglou shrugs and turns back to furiously frankenstein-ing a half-MarioKart, half-tennis abomination to appeal to his perceived youthful saviours.

—

But, alarmism aside, is Mouratoglou’s wider point right or wrong? Is tennis in trouble?

Meh

The short term answer, at least at the top of the sport, is no, not really.

The ATP’s global broadcast figures (even without including the four most popular events, i.e the Slams) nearly doubled between 2008 and 2018, from 464 million to 919 million, and continue to grow. ATP commercial revenues more than doubled in the same period, from $61.3m in 2008 to $143.4m in 2018. (Source ATP)

In the 18-49 age range, the Tennis Channel led all of US cable with a 67% increase in year-over-year viewership in 2019, while the 25 to 54 year-old group grew 44% in the same period, with an annual household increase of 40%. The network also saw increased viewership in 51/52 weeks and 13% more unique viewers in 2019 than 2018. (Source)

On the ATP’s streaming service ‘TennisTV’, non-live (catch-up) now accounts for between 25 per cent and 50 per cent of minutes consumed, indicating evolving viewing habits, but with the capability to harness and profit from them. The TennisTV platform was one of the earlier examples of a sports association presciently launching their own, native streaming service (launched in 2009).

Roland Garros 2019 saw a 31% year-on-year increase in unique views on the streaming service Eurosport Player, and its official app. The 2020 Australian Open saw a 35% increase on the same metric, and the US Open a 22% increase.

These increases in digital consumption are driven by younger fans, not older. Safe to say that the mythical, typical 61 year old tennis fan is not responsible for much of this growth.

As for in-person fan interaction, 2019 posted the highest attendance for any ATP season on record (4.82m fans on-site in 2019, beating the 2017 & 2018 previous highs). And the 2019 US Open, Australian Open, and Roland-Garros also each had record attendance (part of a larger trend of fan growth at tennis’ biggest events, as below).

If you wanted to mostly separate ATP performance from the WTA, the women’s tour paints a similar picture. For the WTA, globally:

The broadcast linear audience rose 33% in 2019, reaching nearly 600 million viewers overall

The digital audience trended for 42% growth in 2019 compared to 2018

The largest WTA events last year also all saw record attendance

—

The top end of tennis looks, in many ways, to be in good health. If you’re feeling particularly nosey, you can see recent financials & Form 990’s for the ATP here and the WTA here. It’s a pretty safe bet that had COVID19 not reared its ugly pathogenic head and turned 2020 in to what will be a shitshow for all sports fans and associations, tennis would have probably continued to build on impressive recent growth, both digitally and on-site.

A far cry from an impending tennis apocalypse.

—

But

That isn’t to say that tennis doesn’t have legitimate threats, both internally and externally. To do so would be dangerously complacent. To be clear, tennis is certainly not on its death bed, nor close to it. But the notion of this sport being set up to truly thrive in this decade and beyond, is much less certain. This is the crux of what made Mouratoglou’s comments potentially counterproductive: It isn’t that what he’s saying is wrong, it’s that the silly messaging is burying the very supportable discussion that this 160+ year old game does need modernisation, and the ways in which we should go about it.

(Important note: The growth and opportunity at the bottom end of the sport contrasts sharply with the top. The ATP and the ITF have struggled in recent years to work out who should do what in the vital on-ramp to professional tennis, with stories emerging regularly from struggling young, and not-so-young, professionals disillusioned with the self-perpetuating elitist structure. Especially with regard to prize money distribution that doesn’t seem to be filtering through the tour despite its abundant source. This week’s announcement of the US Open, and its COVID-forced lack of Slam qualifying (the premier opportunity of a ranking & earnings boost for many lower ranked players), has not helped this sentiment. This topic deserves its own essay which I will try and write soon, but suffice to say tennis has numerous issues to work out when it comes to its competitive foundations. Luckily for this sport, in the short term at least, these iceberg sized problems are mostly submerged from view from the perspective of the average fan, with the majority of observers only able to see the shimmering, obvious brilliance of tennis’ above-water tip of top-tier tournaments).

So how the hell do you ‘modernise’ a sport anyway?

Option 1: Change Or ‘Improve’ The Format

Mouratoglou’s Ultimate Tennis Showdown (UTS) falls squarely under this option, a bold attempt to gamify and shorten a conventional tennis match. In UTS, players can use cards, like some parallel universe where Hearthstone players actually went outdoors, including preventing their opponent from having a 1st serve (basically a ‘trap’ card), or ensuring that their winners count for 3 points (a power-up). There are 15 second time limits between points and the matches are divided into zippy ten-minute quarters. The format also encourages the ‘personality’ of the players to shine brighter than usual, with plenty of mid-match, mic’d-up interviews, pep-talks from coaches, and a brazen encouragement for the players to let loose with emotion (although presumably in ways which fit with the WWE-style nicknames that each player has been branded with: Stefanos ‘The Greek God’ Tsitsipas or the vaguely offensive choice of David ‘The Wall’ Goffin.)

So far it’s been interesting and definitely a substantial departure in terms of format. But given UTS is an exhibition event during a COVID-enforced professional tennis hiatus, it’s absolutely the right sort of environment to try such bold changes. Mouratoglou deserves significant credit for thinking outside the box, even if this early version of his vision may be a little too convoluted. Watching it feels a bit like a scene from Futurama, in which the main character Fry is trying to understand baseball, and all the absurd ways it has changed, in the year 3000. Fry, slack-jawed and head scratching, as ‘!MULTI-BALL!’ is activated, followed by a hover bike running the bases, topped off by a spider emerging from the bullpen, is the sort of reaction you can expect when a traditionalist first interacts with an experimental format (full clip):

A Brief History of Format Changes In Sport

The desire to tweak formats is not unique to tennis. There are similar debates raging in many traditional sports & games across the globe as they all try to keep up with evolving consumer habits & platform shifts. And within these debates is a near-constant dichotomy between what the casual, newer observers want and what the long-time purists want.

Cricket. Twenty20 (a shortened format) has drawn a mixture of praise and scorn, although it’s generally viewed as a significant net-positive for the sport. Praise in terms of its attractiveness to newer fans, its shorter ease of viewing, and its advertiser/programming friendly nature. Scorn from some of the purists:

Ricky Ponting criticised Twenty20 for being ‘detrimental to Test (traditional) cricket’ and for ‘hampering batsmen's scoring skills and concentration. Greg Chappell ‘feared that young players would play too much T20 and not develop their batting skills fully’. Alex Tudor ‘feared the same for bowling skills’. West Indies captains Clive Lloyd, Michael Holding and Garfield Sobers criticised Twenty20 for its role in ‘discouraging players from representing their test cricket national side’, after Chris Gayle, Sunil Narine & Dwayne Bravo preferred instead to play in a Twenty20 franchise elsewhere and make more money.

Rugby has had a successful shorter-format offshoot since the late 1800’s in the form of Sevens (personally my favourite form of Rugby). Its success has prompted some to wonder whether it’ll end up as more direct competition for the traditional 15’s format:

John Taylor: [Sevens] is in danger of becoming a totally separate game. Ben Ryan, who coached both the England Sevens and the Fiji Sevens, dismisses the idea that it should be seen mainly as a development tool. A few years ago players would spend a year or two with the Sevens squad to improve their running and passing skills. Many international players refined their game on the Sevens circuit including all-time greats such as Jonah Lomu. That is happening less and less. Players have to make a choice: Do they want to concentrate on Sevens or 15s? The techniques and training required are becoming very different. Modern professional players are already pretty lean but the forwards in 15-a-side do need bulk as well. In Sevens that is not required and new training regimes are making body fat levels even lower so they are not able to transfer from one game to the other.

Formula 1. Races were standardised down to a maximum 305km limit in 1989, compared to the much larger allowed range of 300km-600km in the 1950s. And a two-hour limit was introduced in 1974. This change was not only good for the safety of drivers but also for TV programming.

Golf tried gimmicky innovations like ‘Powerplay Golf’, but also has a bunch of more engrained shorter-format tweaks like ‘alternate shot’ for foursomes for e.g (which featured in the recent Woods/Manning vs Mickleson/Brady charity match). The Ryder Cup, a runaway commercial success, also uses a different, team-based format to traditional matchplay. Finally, some of the fastest growing areas in golf are ‘off-course’ activities like Topgolf or Driveshack, which are basically gamified driving ranges (these are excellent entry points for the sport, and tennis should be frustrated it doesn’t have a casual equivalent that doesn’t require a full court and at least two people with their own equipment).

Chess. ‘Blitz’ and ‘Rapid’ variations have exploded with popularity in recent years (more on this further down). Once again, some of its Grandmaster purists are, or were, critical:

“Rapid and blitz chess are first of all for enjoyment.” Magnus Carlsen

“Playing rapid chess, one can lose the habit of concentrating for several hours in serious chess. That is why, if a player has big aims, he should limit his rapid play in favour of serious chess." Vladimir Kramnik

“Yes, I have played a blitz game once. It was on a train, in 1929.” Mikhail Botvinnik.

“Blitz chess kills your ideas.” Bobby Fischer.

“I play way too much blitz chess. It rots the brain just as surely as alcohol.” Nigel Short

“[Blitz] is just getting positions where you can move fast. I mean, it's not chess.” Hikaru Nakamura (this quote is particularly funny given this chess champions recent embracing of, and impact on, chess growth and Blitz chess in particular, touched on below).

And finally, tennis itself has already experienced format shortening with the traditional best-of-5-sets variation now extinct (in favour of best-of-3) outside of the slams. Until recently best-of-5 was still played by the men in Masters 1000 finals (until 2007), the Olympics (until 2016) and the Davis Cup (until 2019). Even the ‘win-by-two-games’ rule at slams has mostly been phased out in favour of a deciding set tiebreaker, largely thanks to giant John Isner’s knack for clinging onto his serve more firmly than a cat’s death-grip as it’s being dangled above a bath. Subsequent new variations of tennis, in the form of Fast4, Tiebreak10’s and Mouratoglou’s UTS (all very short compared to normal tennis formats), are merely an extreme extension in this direction.

The common theme here is that format experimentation in most traditional sports was either at first, or still to this day, criticised for its detrimental, leeching effect on the traditional arm of the sport, or that it wasn’t serious/tough enough. Or both. Common criticisms of tennis’ attempts at new formats are no exception. Mouratoglou being dragged over the coals on twitter is one such example.

There is a worthwhile discussion to be had (another day, this essay is already long enough) about whether newer formats play more of a role complimenting the traditional versions, or destroying them. Cricket, Rugby & Chess have all had significant commercial booms as a result of having these quicker versions of their sports co-exist alongside the traditional. Each of the newer formats count younger demographics and a higher number of casual fans. As such there will inevitably be some symbiosis between the new and the old in the immediate term, as well as some possible cannibalisation longer term. Indeed this may be a good argument for tennis associations actively and enthusiastically working on new formats internally and in partnerships rather than letting it all happen externally, for fear of being eaten alive in the future by a new format/sport outside of their control (*Real Tennis’ stink eye intensifies*).

However, tennis does differ from most other major sport in one key way: none of its currently mainstream formats (best-of-3 or best-of-5) have hard time/play limits. Because of tennis’ scoring system (i.e in theory a conventional game could go on forever, back and forth between Deuce and AD) there will always be uncertainty in when a match will end. Cricket’s Twenty/20 has a simple ‘over’ limit. Rugby 15’s & Sevens have time limits. Formula 1 has a distance and time limit. Fast Chess has a very short time limit etc. For many purists, this mystery of match length is one of the many beautiful things about tennis, allowing twists and turns to weave unpredictable and complex details into the story of the match. For others, especially those concerned with broadcasting optimisation and fan attention spans, this ‘mystery’ is seen as gratuitously old-fashioned that no one has time for anymore. It is not a coincidence that nearly every single experimentation of recent tennis formats have included either No-Ad scoring or tiebreak focused matchplay (and/or strict time limits).

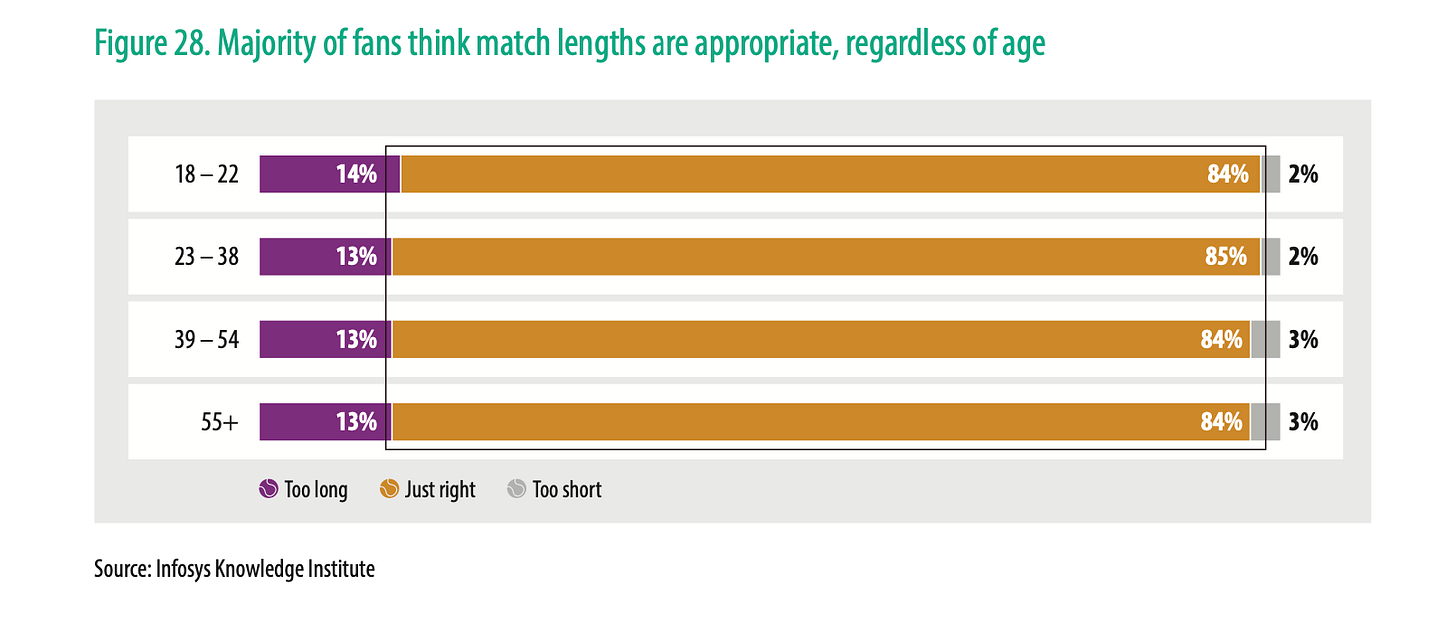

The problem for these sorts of tennis format iconoclasts however, is that the current formats at the top of the game are thriving (as noted further up). The biggest events on both tours are posting record attendance and revenue, good streaming/digital growth, and despite the same ‘mILlenIaLs/gEnZ aNd tHeIr sHiTtY aTtEnTiOn sPaNs’ trope being trotted out occasionally, there isn’t a lot of information to suggest young fans don’t like tennis as it stands once they’re exposed to it (more on this below). One of the only bits of research done on this topic (none of them are particularly good, although that’s part of a wider problem in tennis) suggested younger fans overwhelmingly favoured keeping tennis match lengths as they are:

The lesson when it comes to format then is probably somewhere in the middle of Mouratoglou’s doomsaying and purist stubbornness.

At Mouratouglou’s end of the spectrum, sports having a race to the bottom of fan attention spans, and furiously trying to trim formats, is a bit like bargain supermarkets racing to the bottom of pricing, in which no one ends up winning. The shopper (fan) gets a shitty, unfulfilling product, and the supermarkets (sports associations) make no money and fight furiously for customers with their watered-down, mirror-image competitors. You can posit all you like about sports competing with Netflix or gaming, but perhaps this extreme end of the spectrum would merely be opening tennis up to fiercer competition against these general forms of entertainment. It’s worth at least considering whether some sports should try and differentiate to be deeper experiences in this regard.

At the other end of the spectrum, despite tennis formats clearly showing little need for change at the top of the game, there’s no reason why tennis shouldn’t strive for their own complimentary version of Blitz Chess or Rugby Sevens to try and make the sport wider, i.e more approachable, than it already is. Especially in the lower rungs of the sport (where revenue & growth isn’t so obvious), or running alongside the tours. The Laver Cup is a good early example of what can be done when you throw some tradition out of the window (Laver Cup is team based and heavily emphasises bench interaction & fun) but retain tennis’ core aspects (like scoring for the most part). Or World Team Tennis, which incorporates some scoring tweaks into their own team based, mixed event (which is a lot of fun, if currently America-centric).

Frankly if we ever did get to the stage where a rival version of tennis was gaining popularity sufficiently fast to threaten the entirety of regular tennis, that would probably be considered a luxury in hindsight (just not by the vocal, and currently valuable, purists). After all, there are good reasons Real Tennis faded into the background when Lawn Tennis was popularised. And no prizes for guessing what the purist Real Tennis players and fans thought about the thoroughly modern Lawn Tennis:

I particularly enjoyed this line from a Real Tennis player in the same piece:

“Real Tennis is all about finesse, technique, and last-second adjustments rather than brute power (referring to Lawn Tennis).”

This quote is wonderfully appropriate for the above topic because it sounds extremely similar to the sort of thing you’ll hear muttered from snooty fans of grass court tennis, lamenting the modern brutality and lack of refinement of today’s hard or clay court matches, compared to their pristine, ‘talent-above-all-else’ lawn game. I occasionally wonder if Wimbledon, who routinely enjoy reminding the world that they’re clinging on to tradition above all reason, would be quite so haughty if they appreciated that they themselves had once been seen as modern, sporting iconoclasts of ‘vulgar brutishness’.

History is helpful in this way of reminding us that the inexorable march of time really couldn’t give a toss about our precious purist traditions, especially over a long enough timeline.

Option 2: Entry points & Accessibility

Whilst I don’t think tennis is soon to be confined to the old folks homes of America to the extent Mouratoglou claims, I do think it’s a sport which has become exceedingly narrow in terms of fan discovery and accessibility, both culturally and technologically. This seems to me at least, to be a mostly separate (from format changes), more pressing, and more obvious problem to solve.

If you imagine sport having two characteristics when it comes to fans.

Width: how easy it is for people to first discover and fall into the sport.

and

Depth: how far down the rabbit hole of interest, passion and interaction they fall once they’ve discovered a sport.

Tennis historically has been both wide and deep. Wide because of its international appeal, its biggest events spread across different continents, many linear television networks showing the slams for free or cheap in one’s home country, and superstars which have transcended the game. Deep because true fans who have taken the time to overcome the barriers to entry, for e.g learning & loving the complex scoring system and following the nuanced differences of the various surfaces (hard, clay & grass) and playstyles, serve as passionate, knowledgable and valuable supporters.

Tennis has retained its depth (arguably its deeper today than ever based on the passion and knowledge I see on display in its various communities and tournaments), but it’s inarguably lost a lot of its width for young people in the last 10-20 years. This is despite some of its most marketable stars in the history of the game (Federer, Nadal, Williams’ Sisters, Djokovic et al) playing simultaneously in this golden era.

Entry Points

(This is a simple visual for a helpful way to think about fan interest and discovery in sport. The wider a sport is, the more accessible it is for a person to become a fan, the more entry points there are for fans to ‘fall’ into. The deeper a sport is, the more its existing fans know and care, the more they interact with it, the more likely they are to stick around.)

(NB: I'm aware football/soccer and tennis are leagues apart in plenty of ways that makes comparisons tough and rather unfair on tennis. But football serves as one of the better examples of both a wide and deep game WRT fans, and so contrasts well in this particular context.)

In a ‘wide’ sport like football/soccer, there are plenty of entry points for potential fans to ‘fall’ into: Via its vital and enormous FIFA gaming subculture (which has helped football become both wider and deeper), excellent and culturally diverse grass roots participation (men and women), abundant YouTube/Twitch/TikTok content (professional and user-generated) to name just a few.

Tennis by comparison, has had young and general participation on a downward trend in important regions for years (China is the major outlier). Its participation levels in the UK, despite Andy Murray being arguably the greatest British tennis star in history, are currently lower than badminton, which isn’t particularly surprising given there wasn’t a single indoor tennis court built in Murray’s native Scotland during the peak of his popularity between 2006 and 2016. All of this despite the Lawn Tennis Association’s Scrooge McDuck-sized money pile that they receive from Wimbledon each year. Consequently, the sport is still seen by many as expensive, elitist and rather monocultural. And its visibility in many young sub-cultures is likely weaker now than it has been in years. In particular, tennis hasn’t had a decent gaming culture in a decade. This sports chronically fragmented and individualistic nature, mostly out of short-sighted greed, seemed to nix its promising and critically successful VirtuaTennis and Topspin franchises just as gaming was about to truly enter the mainstream in 2010/11 (tennis gaming hasn’t recovered from this misstep ten years on, and currently badly lags behind most other major sports).

The CEO of Big Ant Studios, a sports game developer, on how FIFA was born and its impact:

Spoiler alert: tennis did not give their game rights away for free (players and agents apparently wanted too much money). And tennis ended up losing vital ground, in terms of cultural relevancy, on many other sports.

For a taste of what tennis has been missing, this is the sort of impact FIFA had on a market which could have hardly cared less about the sport before the FIFA games existed (Source):

Those last few sentences are especially telling. Tennis and football both had simpler, analog fan entry points 30-40 years ago. But they then diverged, with football consistently investing time and long-term thinking into gaming since then, and tennis failing to do so. I don’t think anyone would argue that a FIFA game and a tennis game would have had the same scale of impact, but tennis’ lack of a seat at the gaming table is inescapably a significant reason that this sport has become narrower in terms of accessibility to new, young fans. And its ramifications will run deep and long, given how enormous gaming is, and continues to grow, with regard to 2nd, 3rd & 4th order effects such as inevitable knock-on effects to participation and mindshare in general (not to mention tennis not being in a position to at least try to paddle out to the gargantuan, building wave of esports).

(As a personal and anecdotal aside, Mario Tennis on the Game Boy Colour and Gamecube, Virtua Tennis on the Dreamcast, and Topspin on the Xbox nurtured and supplemented my love for tennis throughout my childhood, alongside being lucky enough to play from a young age. Nothing, on that level of quality or popularity, exists today for kids of a similar age, and hasn’t done so for approx. 10 years. That void feels extremely costly).

Views

Once you have a fan that’s managed to find their way into the early stages of a sports fandom, the most important mission should be to make it as easy as possible to watch and engage with that sport. As gaming and participation are both lagging, you’d think tennis would focus on making watching the sport as easy as possible. Surely, low hanging fruit. Unfortunately, not only are live ticket prices regularly prohibitively expensive for the average young fan, but much more unforgivably tennis’ streaming/broadcast options are a severely bad user experience for many in terms of fragmentation (yes this is a running theme): WTA on TennisChannel and a host of other providers, ATP on TennisTV et al, Eurosport for certain slams, BBC for Wimbledon, national broadcaster subscriptions, Amazon Prime Video for certain events, TennisChannel International launching soon etc etc etc. Many keen fans are required to sign up for an expensive smörgåsbord of slightly overlapping video products if they want comprehensive coverage. Not only that, but that smörgåsbord can be a case of rather all-or-nothing pricing, meaning that if you’re an inexperienced, new fan of tennis and you’d like to watch a tournament, there’s a decent chance you’ll need to at least sign up for a prohibitive monthly or annual subscription to watch. This kind of pricing strategy and platform complexity is an egregious roadblock for new fans (although I hold out some hope that Amazon’s foray into tennis broadcasting may make this less of an issue in the future).

The situation for curious new fans who can’t, or haven’t yet, watched live tennis, and want to check out some exploratory highlights, is even worse. This sports archaic rights-holder agreements mean many classic matches and highlight compilations (the vast majority of which are uploaded from unofficial accounts) are immediately hidden on YouTube due to copyright strikes (despite the fact that other sports associations, such as the NBA, have been claiming monetisation but leaving similar highlights up for years thanks to Google’s Content ID). The Slams in particular, tennis’ four crown jewels of brand recognition, seem to usually only be allowed to offer up meagre 2-3 minute YouTube clips of what can sometimes be 5 hour long matches. Outside of YouTube, there’s also a similar block on anyone seeking to add commentary and analysis to short tennis clips to be used on Twitch, the live-streaming site (which counts one of the most engaged young user-bases on the internet, and was responsible for much of F1’s and Chess’ recent growth). If you imagine this whole process as tennis’ welcome mat, encouraging someone new to the game to walk across the threshold of fandom, it would spontaneously combust the moment a foot hovered above it. That fan could then saunter over to many other sports, who may as well be rolling out a non-combustible red carpet in comparison.

Side note: I’m writing a separate piece on this, but I’ve long wondered if the ATP/WTA/ITF could provide better, and more relevant, media training to lower ranked players in the Challengers and ITF events (or just the player body in general). It’s pretty straightforward to livestream practice sessions, and perhaps even some lower-rung matches (pending video rights), on Twitch/YouTube from an iPhone/Android. If enough players did so, inevitably a few stars would break through from the lower levels, potentially bringing with them a legion of next generation fans from one of the younger platforms (Lando Norris a great example of how this can work in F1). Tsitsipas and his YouTube channel was a good early example, although his videos (as opposed to streaming) require serious production time that most players don’t have. The ability for players to be the masters of their own story, with regard to how they’re seen (and how often) by the public, is especially pertinent in tennis, which is famously restrictive when it comes to media access to top players.

Tennis needing to sort out its ease of viewing is especially critical at a time when consumption habits have already changed substantially, and continue to do so. Twenty years ago channel surfing discovery enabled plenty of accidental first exposure to tennis on TV (I’ve met an uncountable number of fans who stumbled onto the Federer vs Nadal Miami match in 2004, or similar, by complete mistake as a kid, absent-mindedly switching between channels, and were unintentionally left mesmerised by what they saw). This no longer really exists to the same degree these days, with dedicated streaming services requiring more intentionality of viewing rather than passive channel switching. So how much does this hurt the volume of next generations fans? And how does tennis capture these lost, passive viewers? A rethinking of pricing, platform complexity and discovery is essential. Off the top of my head:

Unified streaming platforms (or at least less fragmentation).

Copy the NBA’s friendly approach to fan-made highlights & content, ideally on the back of modern, rewritten rights-holder contracts when they’re up for renewal.

Innovate with the TennisTV platform (The ATP are in a pretty unique position in major sport in terms of having an ‘in house’ international streaming platform). Possibilities include clip/highlight sharing from within the apps/browser (a la Twitch), meaning fans could easily share an officially credited clip on social media (which could also be used to convert non-customers to paying TennisTV subscribers with a few user interface tweaks).

Single match micro-purchases, favourite player subscriptions, ‘tournament/surface passes’, cheaper ‘next-gen pass’, cheaper ‘doubles-only pass’ etc. $100+ a year for TennisTV or TennisChannel+ is seriously prohibitive for brand new fans.

Consider streaming Challenger matches free on YouTube/Twitch (they’re already available on the ChallengerTV website and Vimeo, but both have limited discovery tools and traffic). Not only could this help give the lower rungs of the sport some additional attention, but it could also enable young players to stream their own matches and build their own channels and communities early without needing to put in a lot of content effort.

Loss-leader pricing with some of the biggest matches shown free to increase awareness (for e.g streaming the ATP/WTA Finals final on YouTube just as football streams the Champions League final on YouTube). The ATP already has another great opportunity to test this out given they’ve already sold the rights to all their biggest events to Amazon in the UK via Prime Video. How about livestreaming the first ATP Finals match of each day for free on Twitch as a loss leader, and then streaming the 2nd match behind a Twitch Prime subscription to see how well it converts free to paying fans from a slightly different platform demographic (Twitch as opposed to Prime Video).

Etc etc etc…

Anything to make that welcome mat less combustible.

Lessons Learned?

The COVID19 hiatus has uncovered an uncomfortable truth for many sports, including tennis. It revealed which areas of the sporting world could rely on diverse areas of fan interaction and entry points, and which couldn’t, as most athletes and fans had to lock themselves away at home and isolate. Winners included F1, with its million+ viewer Virtual Grand Prix's & new fan exposure via streaming and Twitch, again, enabled by the presence of a well made, complimentary game in ‘F1 2019’. McLaren driver Lando Norris in particular has pulled in 100k concurrent viewer streams during COVID lockdown, bringing in legions of new, young fans. As well as the second season of Netflix’s Drive To Survive documentary. For Football, it was thanks to FIFA, its accompanying esports events, and ever-entrenched presence in the cultural zeitgeist. For Chess, it was the success of the Queen’s Gambit on Netflix, alongside suddenly becoming the meta on twitch, attracting hoardes of young fans by way of a, now daily, exposure of the 1500 year old game on LivestreamFails (yes that is the most absurd juxtaposition I’ve ever written). Chess.com expects a hard-to-fathom 10 years(!) of growth, in terms of player base and games played, smushed into just the past 3 months, owing much of it to its ‘Fast’ Chess format variations. If you were plotting Chess on the Deep/Wide graph the change would look something like this (below): with Netflix, Twitch, the Blitz Chess format, and Hikaru and Alexandra Botez in particular, responsible for the widening, creating brand new, non-traditional entry points for potential fans to fall into -

On a related note, the Golf world would have been mostly silent during COVID had it not been for the non-traditional format charity match between Woods/Manning vs Mickleson/Brady, allowing a cross-pollination of two major sports thanks to a format tweak that helped vastly different skill levels play together. Again, another tick in the ‘pro’ column for complimentary format experimentation.

…

And then there was tennis, most definitely a loser in this regard. They tried bravely to put on an esports event in Madrid, which unfortunately just served as a lesson of how far this sport is from many others when it comes to gaming:

For context, F1’s virtual Bahrain Grand Prix’s peaked at 396,000 concurrent viewers on Twitch (plus hundreds of thousands more on FB & Youtube, and millions on linear TV), while Tennis’ Virtual Madrid Open peaked at 19,000 viewers on Facebook, with most engagement focusing around how poor the game, TennisWorldTour, looked and played.

Tennis also tried fantasy brackets, which worked well from what I saw. And existing TennisTV subscribers were given free access to the service during the hiatus (a welcome move).

But it all felt a bit sad, watching such an amazing sport brought to a standstill of interaction and fan growth while more adaptable, yet similarly old, games rose to the occasion.

Cautious, But Proactive, Optimism

Tennis, as outlined in the first half of this essay, is in rude health in many ways. It’s still a hugely successful, global sport with legions of passionate & knowledgable supporters. It remains a fascinating and deep spectacle, and is still attracting young fans despite, at times, trying rather hard not to. But outside all of the truly good news about the health of this sport, lie inescapable problems that need proactive solutions. Whilst format experimentation is almost certainly a good idea when one considers how valuable it would be for tennis to incubate its next big growth-spurt from within, rather than be cannibalised from the outside, I continue to wonder whether too much of the talk surrounding modernisation is focusing on the less pressing of the two areas. I’d venture that a successful sport being 'young' probably has much more to do with having a wide, culturally varied funnel of discovery and participation for fans and players, rather than just a race to the bottom of attention spans.

Tennis almost certainly has significantly more flexibility, both in terms of generating revenue and fan demographics, than Mouratoglou’s sweeping statements seemed to suggest. But that doesn’t mean that the general direction he’s pointing towards is wrong, nor that the precious flexibility is unlimited. My hope is that anyone reading this considers that tennis needs to start having more self-aware conversations about the very real and varied ways in which this absolutely wonderful sport is falling, and has fallen, behind.

And then get to work.

As Bjorn Borg once said, simultaneously cryptically and obviously:

The ball is round, the game is long.

Boy would it be nice if this particular game went on for as long as possible.

—

Thanks for reading this unusually long essay. You can find me on Twitter here and you can sign up for this publication, The Racquet, here:

Great read, thanks. I consume a lot of sports journalism and often think that tennis lacks these sort of long form, analytical pieces compared to lots of other sports like football, cricket, golf. Tend to just get a lot of match reports, and predictions.

Completely agree when it comes to video games. I love watching a variety of sports, playing them and playing video games. I used to play Virtua Tennis loads on the PSP. But it has always annoyed me that tennis hasn't had a good video game for a whole console generation, and longer (Can add golf to that too). During lockdown I have continued my consumption of F1 through the virtual gps, and got to know the drivers better as they all live stream on Twitch, and have kept this up in between races too. It has felt like great marketing for F1 throughout and also been nice to get to see more of their personalities.

F1, like Football, also has a huge youtube presence with lots of popular accounts related to the F1 game or other motorsport games, which have also been really popular during lockdown and help to drive interest. Some of these guys featured in the virtual gps, one of them commentated, and they regularly interact with the official F1 account and the Codemaster's account on social media. It feels like the various elements are all in sync working together to market the sport and drive interest. Even something like them just releasing driver ratings for next year's game has seen huge fan engagement and debate online, similar to FIFA's ultimate team.

In addition, F1 (since Bernie Ecclestone left) has a fantastic youtube acount which updates regularly with various top 10 videos during the season, and unseen camera angles etc post races. They have lots of interviews with past drivers, and during lockdown have uploaded full classic races at a set time so people can watchalong together and comment. They also always have content for key anniversaries, and do a great job of having lots of old clips to educate fans, and celebrate the legends.

They have also set up an official F1TV website where more hardcore fans can subscribe to watch all the races, have access to every race stretching back to the 80s, as well as some documentaries.

In summary, completely agree there is so much more tennis can do to engage fans, and bring new ones in and what F1 has done in the last few years in particular is a great example of what is possible.

Man I have missed your articles and this reminded me why. Excellent analysis.

One point you made about tournaments being widely accessible to everyone around the globe is I think only true to a degree.

There was I think only one 250 tournament and only one challenger in the whole of Africa last year. Countries like India do have a tournament but it's a 250 where not many recognizable stars come. It's clear that the organizations are gravitating more towards big-money markets like China and Singapore which is fair enough but it does make it harder for people in those other countries to get interested in tennis especially when as you say there are so many different competitors.

Tennis, also I think starts out with a disadvantage. Football you can just take a ball and play, same with basketball. Chess and cricket also don't cost too much. Tennis on the other hand does require rackets and a court, leading to it being considered a elitist sport, though maybe not on the level of golf. Again here comes the point of accessibility. I've heard of people "just going out for a hit" in the USA and other western countries but that is simply not possible in less developed countries like it is in those above mentioned sports.

Anyway, I don't know if I have contributed anything to the above topic but these are just some of the thoughts that came to my head while reading your (once again excellent) article.