Wimbledon Bans Russians and Belarusians

Individual vs national identity in tennis, 'pocket knife' sanctions, precedent, and Wimbledon's justification

Wimbledon has barred Russian and Belarusian players from Wimbledon due to Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

The LTA have done the same for their grass warm-up events in the UK (covering Queens, Eastbourne, Nottingham, Birmingham, Surbiton, and Ilkley). Considering those grass warm-up tournaments fall under the ATP or WTA, challenges to that decision may be imminent. But for Wimbledon, unless ‘circumstances change materially between now and June’, three of the top 20 singles women and two of the top 10 men, along with many others further down the rankings, will not be allowed to play the most high profile event in tennis because of where they were born.

The reaction has been split, but mostly negative.

WTA: Individual athletes should not be penalized or prevented from competing due to where they are from, or the decisions made by the governments of their countries… A fundamental principal of the WTA is that individual athletes may participate in professional tennis events based on merit and without any form of discrimination.

ATP: "We believe that today’s unilateral decision by Wimbledon and the LTA to exclude players from Russia and Belarus from this year’s British grass-court swing is unfair and has the potential to set a damaging precedent for the game.

The ATP and WTA vigorously disagree with Wimbledon’s position. But outside of threatening to temporarily strip Wimbledon of ATP/WTA ranking points, the only real leverage those organisations have over the all-powerful Slams, it’s unlikely that anything too meaningful will be done in retaliation. The Slams account for nearly 60% of tennis’ total revenue and have always acted like large omnipotent islands that surround the tennis ecosystem.

In the other direction, Ukrainian players have supported the move. While some Russian players and their teams have signalled support for Ukraine, either in the form of wearing Ukrainian colours or signing ‘no war please’ on the camera lens after matches, Ukrainian players like Marta Kostyuk don’t see this as sufficient action to the backdrop of Putin’s atrocities:

Kostyuk: You can't be neutral in this situation. For me, "No war" can mean several things. For example, we (Ukraine) could end the war by giving up. But that was never an option. From day one, I knew it wouldn't happen because I had lived through the revolution and I knew that people wouldn't want to go the other way, which was to Russia. So today to say "No war", for me it means wanting Ukraine to give up. Because Putin will never stop, everyone knows how crazy he is. So we fight.

Kostyuk, Svitolina and other Ukrainian players sent out a joint statement yesterday:

We noticed that some Russian and Belarusian players at some point vaguely mentioned the war, but never clearly stating that Russia and Belarus started it on the territory of Ukraine. The very silence of those who choose to remain that way right now is unbearable as it leads to the continuation of murder in our homeland. We demand that the WTA, ATP and ITF make sure that players who represent Russia and Belarus answer the following questions: 1. Do you support Russia's and Belarus invasion in Ukraine's territory and as a result of that the war started by those countries? 2. Do you support Russia's and Belarus military activities in Ukraine? 3. Do you support Putin's and Lukashenko's regime? If applicable, we demand to exclude and ban Russian and Belarusian athletes from competing in any international event, as Wimbledon already done. There comes a time when silence is betrayal, and that time is now.

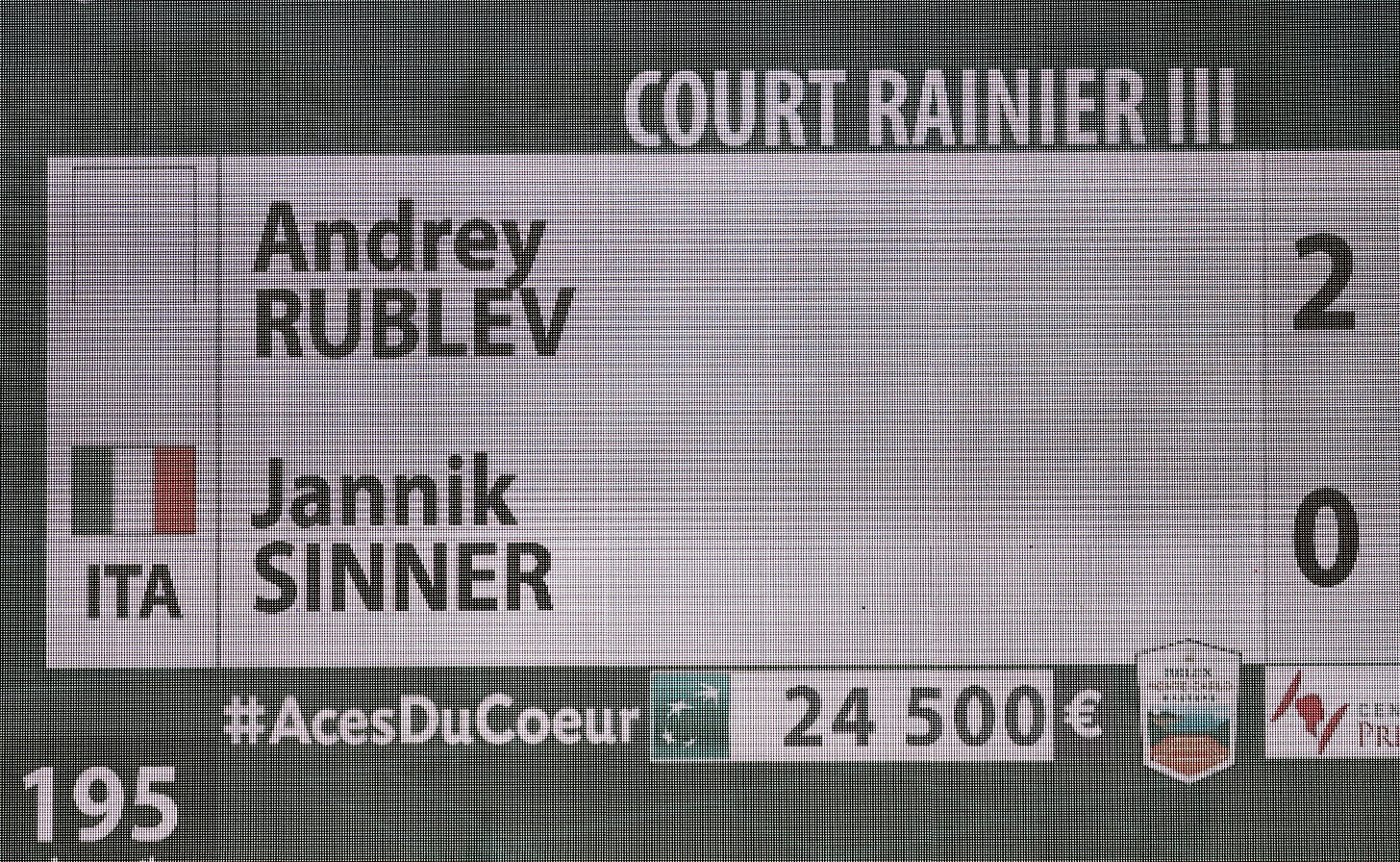

What Kostyuk is asking of Russian and Belarusian players is unfortunately incompatible with what most of those players can and will do. Daniil Medvedev may live in Monaco but has much of his family in Russia. Andrey Rublev lives in Moscow. Publicly rebuking Putin’s actions would be dangerous for any Russian player regardless of how distanced they are from the regime. Russia's parliament passed a law in March imposing a jail term of up to 15 years for spreading intentionally "fake" news or statements about the war. Any public opinion made by these players would be high risk.

This is not to say that the Ukrainian players are wrong. Their friends, families, countrymen and women are being slaughtered by a despot. While large parts of the rest of the world watch this war unfold, safe at home and able to wield privileged opinions about ‘fairness’ over who plays a damn tennis tournament, Ukrainians are dealing with more visceral realities of dismembered children, mass murder, and the destruction and displacement of their homeland and people.

Ukrainians are right to feel as though close geographical cousins, and those further afield, should do more to help. And Russian individuals are right to feel caught in the crossfire of politics that utterly dwarfs their own agency. Easy answers are few and far between among the complex systems that participate in, and enable, wars.

The question here is whether Wimbledon’s decision was right, whether it helps, and whether it was communicated well.

Individual vs national identity

Tennis had already banned Russia from competing in team competitions, both in the Davis Cup, where they are the reigning champions, and the Billie Jean King Cup. And Medvedev, Sabalenka and others had already been playing without a flag next to their name for months.

What has surprised many tennis fans about Wimbledon’s decision is the targeting of individual athletes rather than their collective national team participation. After all, Russian NHL or football players are not banned from playing for their domestic clubs in various countries despite being banned from national competitions, nor are Russian boxers banned from competing for major individual titles in most countries. And tennis has always internationalised its players to an extent. Sovereign stars travelling the world competing more like no-home CEO’s of their own careers rather than explicit, sporting representatives sent on behalf of, or closely tied to, their country. While rhythmic gymnastics, for example, is run by the wife of one of Putin's closest oligarch backers, Alisher Usmanov, and many of its competitors enjoy close relationships with Putin (some of who have participated in a pro-war rallies and gestures), current Russian tennis players are comparatively independent of the Kremlin, both in terms of relationship and funding.

But while player’s individual rather than national identity is the focus for many tennis competitors outside of the Olympics or team competitions that make up the minority of tennis tournaments, flags are still raised and national anthems are blasted if they win the biggest titles. Wimbledon clearly didn’t want that symbolism in play should a Russian win Wimbledon in a few months time. Russian F1 driver Nikita Mazepin met a similar fate after being dropped by his team altogether due to his nationality and sponsorship from Uralkali, a company run by Mazepin’s father Dmitry.

To be clear here, both scenarios would have been used by the Kremlin. Wimbledon banning Russian players merely adds to the ‘us against them’ propaganda pile to retain domestic support for Putin’s goals in Ukraine. And if a Russian player had won Wimbledon, Putin would have been keen to lean on the narrative of sporting prowess in a hostile land as a proxy for enduring Russian strength and relevancy. Hypothetical Wimbledon champion Andrey Rublev would have had little say in the matter if Putin wanted to use him as a publicity pawn in his game. It’s tough to answer therefore which direction would result in a ‘better’ outcome.

The goal and efficacy of sanctions

The goal of sanctions are often opaque. Putting pressure on a warmonger is a broad mission and these goals are set by governments and military intelligence, not tennis clubs.

Conventional trade and financial sanctions result in meaningful behavioural change in the sanctioned country about 40% of the time. The success rate is maximised when sanctions are imposed in a coordinated, international effort, with very specific security goals rather than broad missions such as total regime change. But sanctions are also historically less effective when targeting large autocracies rather than smaller democracies, with dictators less likely to be swayed by the suffering of their citizens as long as they can manage information flow and retain power. Sanctions have even historically pushed larger autocracies into increasingly autocratic, isolationist behaviour especially in the short term, hurting their populaces further.

The majority of the damage that sanctions create is focused on high-cost economic measures, the likes of which the UK, US, and parts of the EU have already implemented. If those heavy economic and technological sanctions are the ballistic missiles of non-military moves to limit the power of a hostile country, then preventing players from playing in a tennis tournament barely even registers as a soldier’s pocket knife. But sanctions should be viewed in aggregate rather than in isolation. There is an ‘every little helps’ argument in play here considering part of the stated goal of these sanctions is to make Putin’s Russia a pariah state.

Whether or not sanctions work will almost entirely rely on whether ‘the West’ can impose those heavier penalties in unison, and for an extended period. This is far from certain. Germany for example has resisted directly supplying tanks and other heavy weapons to Ukraine and crucially has opposed an embargo of Russian oil and gas, the lifeblood of Russia’s currently war-sustaining economy. Whether sanctions will have a meaningful effect on Putin will have infinitely more to do with cohesion among those allies on major issues than the threat of Daria Kasatkina lifting the Venus Rosewater dish on Centre Court. But could a Wimbledon ban make a difference, even if that difference is infinitesimally small? Perhaps. It’s nigh on impossible to quantify the impact of isolated sporting sanctions like this considering the scale of what is unfolding in Ukraine and the international response.

Wimbledon have decided it’s better to do something, even if that something is minuscule in the grand scheme of things, than nothing. And it’s difficult to say for sure that the game theory underpinning that position is a bad idea. Russian authorities and politicians have already responded with anger to Wimbledon’s decision. Does that mean anything material?

Leader of the Communists of Russia party, Sergei Malinkovich: “I think they will pay for this. There is a feeling that soon there will be no international tournaments, there will simply be no Olympics in Western countries, and tournaments will be held in Moscow, Beijing and other cities, but not in the West.”

Deputy of the State Duma, Dmitry Svishchev: “Great Britain is known for its vivid anti-Russian statements and position not only today, but always… Wimbledon, the oldest tournament in the world, lives by its own rules and principles. This decision has nothing to do with sports. It’s politics and money. This is what rules Wimbledon now.”

Sanctions are an imperfect tool, that often do not result in desired outcomes. But they are a relatively modern weapon, deployed to try and avoid direct military casualties and overly-quick escalation.

Precedent

The example most often given for sporting sanctions being effective in producing positive change in very recent history is the sporting ban of South Africa during Apartheid.

Goolam Rajah, General Manager of the South Africa cricket team: “One has to be able to look at the big picture and there is always a price to pay for attaining what is "right". The vast majority of white cricketers who couldn't play against the best teams in the world during our 21-year period of isolation were innocent but that was a very small price to pay for the emancipation of 40 million people.’

But there is dispute about which particular sanctions and areas of pressure actually brought about change in South Africa…

“It is concluded that sport fulfilled an important symbolic function in the anti-apartheid struggle and was able to influence the other policy actors, but generally to a far less significant extent than is usually asserted.”

South Africa’s change was heavily influenced by movements like black schoolchildren taking to the streets of Soweto in 1976, catalysing years of un-ignorable protests that made the country essentially ungovernable until the right political and international pressures allowed productive reform. Pinning such change on narrow cultural sanctions like sporting boycotts or bans is simplistic. Productive change therefore is often a tangled basket of actions, with efforts to tie cause and effect difficult. But you would struggle to find many who denied the impact of those sporting sanctions entirely.

So does this make Wimbledon’s ban of Russian and Belarusian players more or less justified?1

Wimbledon’s justification

Wimbledon’s statement justifying the Russian and Belarusian ban included the following section:

In the circumstances of such unjustified and unprecedented military aggression, it would be unacceptable for the Russian regime to derive any benefits from the involvement of Russian or Belarusian players with The Championships.

I’m not sure who on earth conceived of this sentence, but it’s a terrible framing of the issue and motivations at hand. Countless nations have committed atrocities via military aggression throughout human history, including what is estimated to be hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians killed by the UK and the US over the past twenty years, by two countries who own or control so much of major sport that they are largely shielded from any threat of sanctions. This justification reads like state sponsored propaganda, regardless of purity of intention, and helps neither Wimbledon nor Britain. Both tournament and country aspire to be better than that.

There are multiple arguments, as noted further up, for limiting Russian benefit from cultural shows of strength around sporting glory. But when it comes to communicating the rationale behind those arguments Wimbledon are guilty of poor judgement. This is not the moment for erasing the bad of human history in order to place Russia as the evil of all evils, it is the moment to acknowledge the catastrophic damage to human life that Putin currently and directly causes and to unite around trying to limit harm to those civilians via whatever route possible. Sanctions, both major and trivial, are a modern yet still imprecise tool to limit that harm, both over the short and long term.

The statement also refers to Wimbledon' ‘taking into account guidance set out by the UK Government specifically in relation to sporting bodies and events.” This is understandable but raises the question of why this couldn’t have been mandated at the state level rather than having a bunch of gentlemen in a tennis club board room voting on the decision. Especially without more alignment with other tennis organisations across other countries with similar stances on Russia.

Fallout

The ATP were correct in noting that Wimbledon’s move creates a slippery slope problem for tennis. Will Wimbledon et al ban Chinese players if China invades Taiwan in the coming years? Do bans like this depend on who the aggressor is? Russia, despite its noisy demonstrations of strength and military barbarity, has a smaller GDP than Texas, and has been waning in relevance and power for decades. It’s easier to sanction and show strength against Russia than it will be against China (although the WTA have shown bravery here), despite both being autocratic regimes at odds with much of Western democracy. Are these stands going to be consistently principled or conveniently circumstantial?

Russian cats have been banned from cat shows. Russian trees have been banned from European Tree Of The Year Contest. Stolichnaya vodka was boycotted by bars and even had to change its name to Stoli, despite the brand being based in Latvia and the owner Yuri Shefler having been exiled from Russia since 2000. Perhaps Wimbledon’s ban is the latest ineffectual pocket knife in a battlefield featuring ballistic sanction missiles. Or perhaps every weapon, no matter how small, is needed for the cause to bring about change in Putin’s crumbling, yet still lethally dangerous, fortress. I don’t have a good answer to which scenario is right, and I would be skeptical of anyone who had a confident answer considering the tangled, overlapping weave of sanction efficacy. I do know that this is not the time to criticise ordinary Ukrainian citizens for their calls for help. I would be desperately shouting from the rooftops demanding similar in their position.

As tennis fans we all like to think this sport is important. But to a backdrop of war it’s an irrelevant, yellow, spheroid-shaped speck on the map of all humanity. Wimbledon have decided to act, albeit in their own flawed way. And it’s unlikely we will ever know whether that speck contributes to the momentum of change. For the sake of the people of Ukraine, who are still being murdered while we debate the notion of being able to play tennis, we hope that change happens at all.

— MW

Twitter: @mattracquet

I’ll see paid subscribers on Sunday for Barcelona/Belgrade or Stuttgart final analysis.

The Racquet goes out twice a week, a (free) piece every Thursday/Friday and a (paid) analysis piece every Sunday. You can subscribe here (first week free):

Top: James D. Morgan/Getty

Most recent:

For historical context, South African players continued to compete on the pro tours and were not banned by Wimbledon during Apartheid; Johan Kriek and Kevin Curren both reached Grand Slam finals.

This comment is benefiting from coming after your thoughtful post, Matthew. Per Chris Clarey and Ana Mitric, Andrei Rublev says players (or, just him, it's not totally clear) offered to donate their prize money from playing as an alternative to the ban. This seems like a good idea, to me, but perhaps there are mitigating circumstances I don't see right now.

At any rate it would avoid one hitch in the ban's consequences I've yet to see mentioned anywhere: banned players will lose both points that drop off and the chance to replenish points. From the perspective of their "jobs" that's more consequential than prize money, at least for the top earners.

That's a thoughtful post. As Matthew states, there is no obviously wrong or right answer here, and I'm glad he raised the thorny topic of Western countries blithely ignoring their own aggression. If you were going to extend this argument to its logical conclusion, no player from any nation would be allowed to play.

Sadly, I think Wimbledon and the LTA have got this wrong. If anything, it plays into the "them against us" message that Putin is so effectively pedalling. It punishes individuals who are probably (but who really knows) scared to speak out, and if I was in Rublev's shoes, or Sabalenka's, then I would be angry.

In the end, though, it's a tiny gesture that will hurt some individuals but will also offer some solace to the Ukranian players - and people - who will be feeling the weight of silence from elsewhere.

So, like Matt, I end up conflicted. I feel sympathy for the affected players, and sorry for the paying public who will miss out on the brilliance of Medvedev etc, but equally feel that Ukranian players need to feel supported by the authorities.

Ultimately I think the LTA has made a mistake (as do others I spoke to at my local club last night). I understand what it was trying to do but an outright ban is not the way to do it.