Daniil Medvedev Does *Not* Like The Clay

Do flatter hitters have it tougher on clay? If so, why?

Daniil Medvedev, before unfortunately testing positive for COVID and having to withdraw from Monte Carlo, gave a very funny interview about clay courts. After apparently getting taken to the woodshed by Rafael Nadal in a practice session on Sunday, the Russian had this to say (originally in French):

“Honestly, there's nothing I like on clay. There's always bad bounces, you're dirty after playing. I really don't enjoy playing on clay.”

(you can watch some of the practice session here)

Aside from Medvedev channeling Anakin Skywalker…

…I don’t blame him. Playing Nadal on clay is probably one of the more humbling professional experiences one could endure. But this also speaks to Daniil’s sometime trouble on this surface.

While I actually think Medvedev is a bit underrated on clay (even by himself apparently), there are some reasons why flatter hitters can have it tougher on this surface. Serve impact aside, the trajectory of their groundstrokes get riskier the further back in the court they are compared to heavy topspin hitters. And the physics of the bounce is also less kind to them than it is on quicker hard or grass courts.

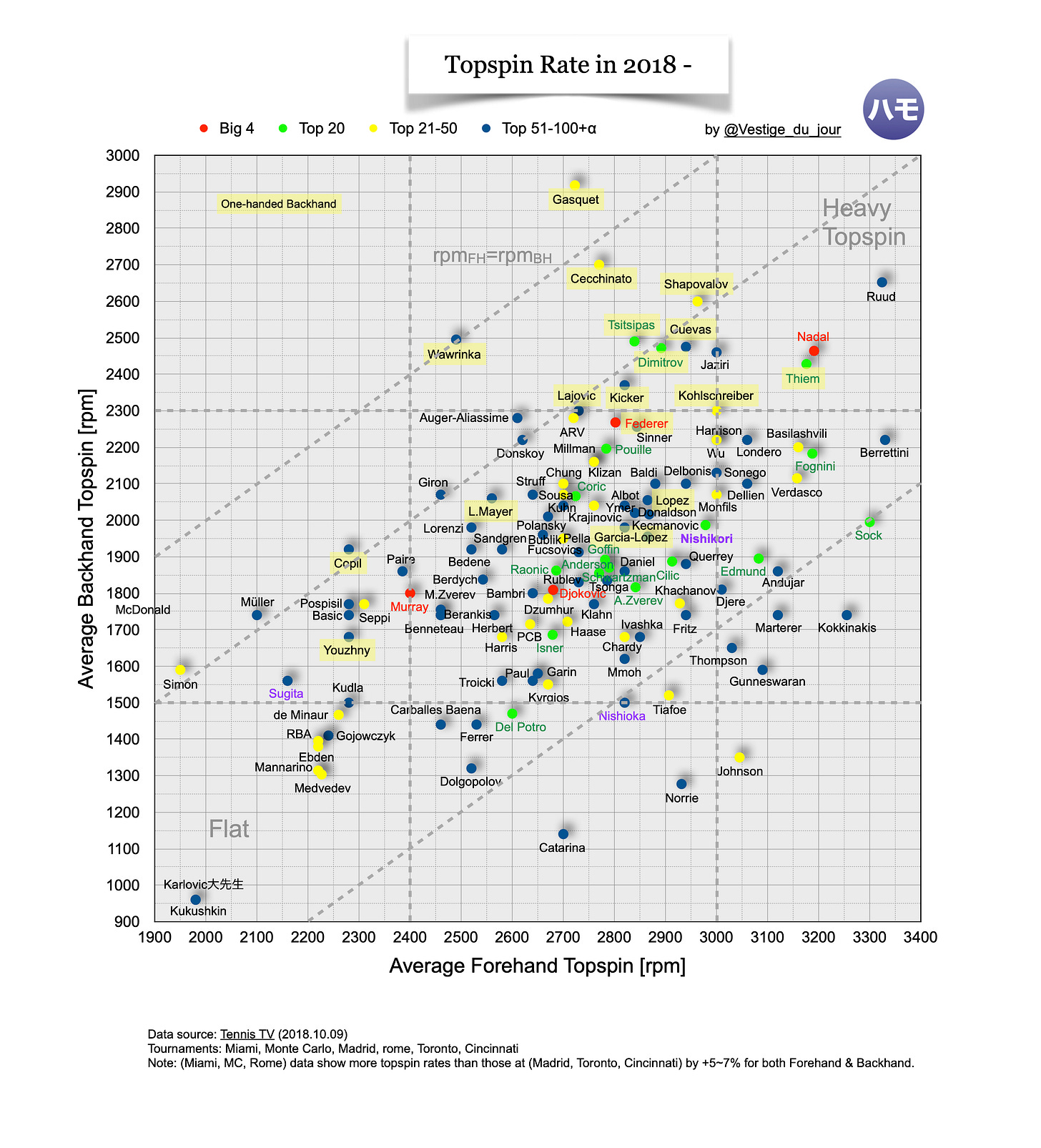

A fun experiment is to have a look at the spin rates on the men’s tour and see if there’s any connection, however loose, between a lack of spin and performance on clay.

If we take the bottom left section, i.e the very flattest hitters on both forehand and backhand, and look at their win rates across each surface, we get something interesting but maybe not particularly surprising.

All eight of the flattest hitters on tour count clay as their worst surface:

Now there are a few problems with some of this data. A few of these players come with very small sample sizes, for example De Minaur has only played 13 tour matches on clay and 10 on grass in his relatively young career. And Ebden, despite being 33 years old, has only played 14 main tour matches on clay in his life! For some of these players they’ve clearly prioritised playing on their stronger, which usually means quicker, surfaces. However quite a few of the others have played enough on all surfaces to draw at least some rather loose conclusions from all this.

At least for the very flattest of the hitters on tour, the pancake boys, clay does seem to be a weak spot.

Trajectory

You can go down a very deep rabbit hole of physics on this topic. But I’m going to try and give the most high level, TL;DR version as possible to keep this light. If you’d like to read deeper, I recommend this great piece on ball bounce physics by @FogMount, further work by Rod Cross here, and this paper on ball flight physics.

First of all — the trajectory of the ball.

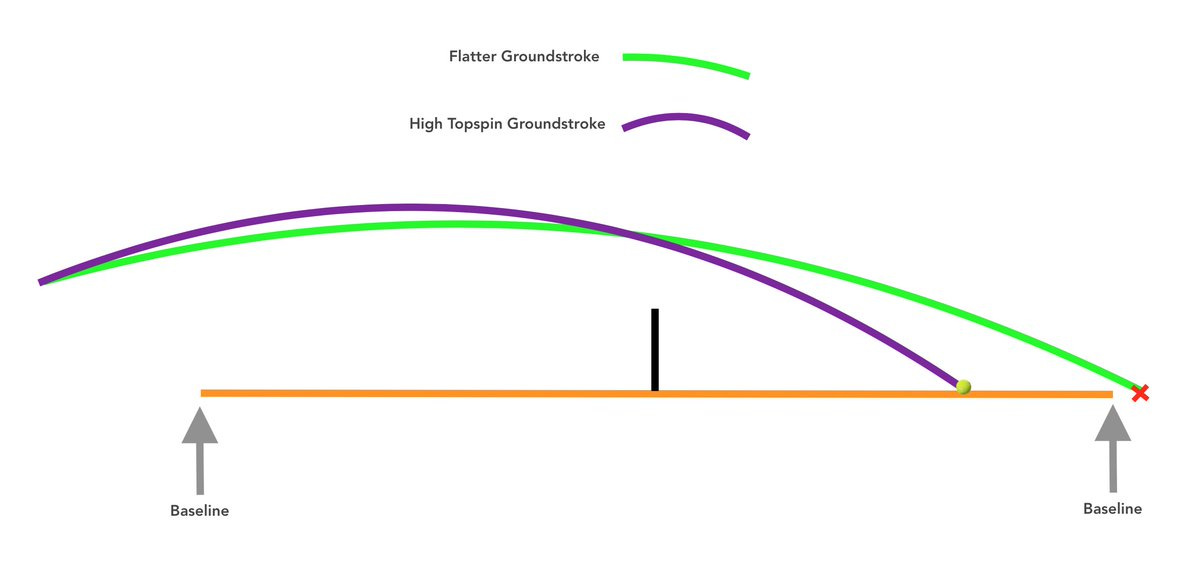

Heavy topspin hitters will have more of a low-to-high swing path and higher launch angle (ie the angle the ball leaves the racquet at on contact). And the flatter hitter will have a more horizontal swing path and a lower launch angle. While taking an aggressive position inside the court, both flatter and high-topspin hitters should usually work fine (flatter hitters are arguably more effective given greater power and depth). Both trajectories leave the ball with a good chance of clearing the net and then landing before the baseline:

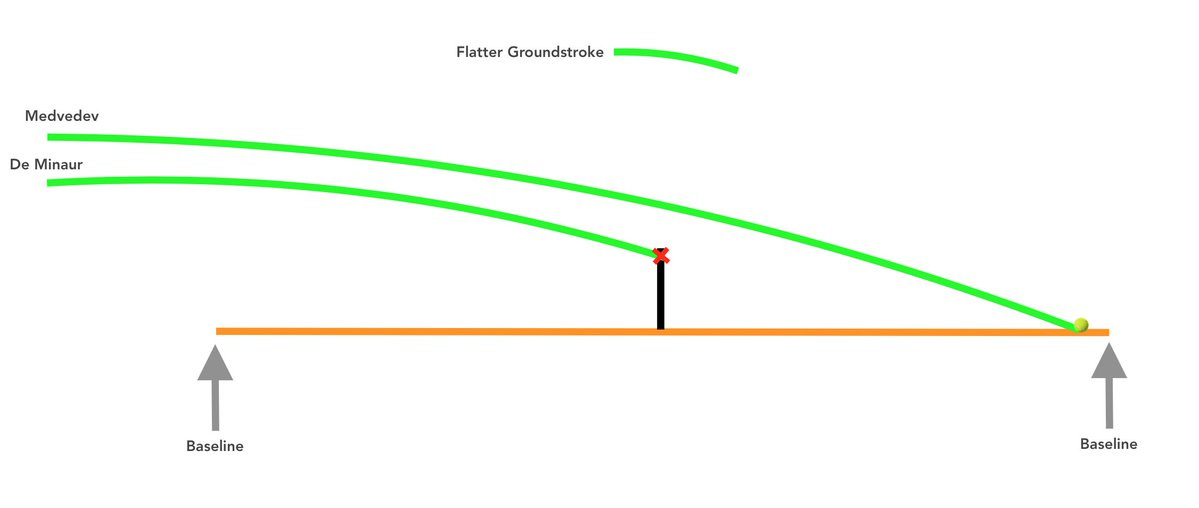

But when pushed further back in the court, as players on clay regularly are, flatter hitters have less margin to work with from deeper positions. If they hit the same sort of shape & power (as they did from inside the court) from further back, they'll end up in the net...

...and if the flatter hitter compensates by hitting bigger or by giving the ball a bit more height to clear the net, they then have an increased chance (compared to a high topspin player) to hit the ball out:

As a result, flatter hitters do not have the same breadth of options as heavy topspin hitters from deep in the court.

All shots experience drag through the air, but the Magnus Effect creates a greater downward force on topspin shots, meaning those who hit with greater topspin can hit hard & high while relying on greater downward force (compared to flat hitters) on the ball to drop it in the court before it reaches the baseline, giving it more vertical speed.

This is also why the slice, or backspin, is such an interesting shot in tennis. A backspinning ball experiences the opposite version of the Magnus Effect, i.e an upward force rather than topspin’s downward.

Side note: This is why the very best slices on tour, for e.g Federer, find the best balance between a downward (or high to low) swing-path on the ball, coupled with a strong backspinning Magnus Effect, giving it sufficient upwards force to initially clear the net before succumbing to drag and gravity. The result can be slices that appear to cut through the air quickly, initially rising slightly, and then landing deep in the court:

Flatter hitters like Medvedev therefore don’t have the Magnus Effect helping, to the same degree as heavy topspin hitters like his Monte Carlo practice partner Nadal, when it comes to helping their balls dive-bomb (at a higher vertical incidence) to stay in the court. The evolution to polyester strings, and the large racquet heads containing them, of the last 30 ish years have enabled players who use heavy topspin to swing and hit the ball very hard and very high over the net, and yet be consistently safe from hitting the ball long. This is a large reason for the aggressive baseliner playstyle meta that has developed and dominated over the last few decades. Björn Borg & Thomas Muster were some of the earlier trailblazers when it comes to high margin groundstrokes. But the changes have only accelerated since the 80’s & 90’s, first with Federer’s forehand (2800 avg RPM), followed by Nadal (3200 avg RPM) and Djokovic, all bringing extraordinary elements of high margin offence and defence. Clay, as the slower surface on tour, counts high margin offence as particularly important, with Nadal’s high spin rates on his forehand in particular a wonderful example of how utterly 3D modern tennis can be.

If you imagine all tennis looking the same from an aerial shot, a ball travelling back and forth in straight lines from one player to the other — like the very obviously 2D ‘Pong’ — then Nadal, practically the ‘spinniest’ of players, is the example who when you pan down to court level, you suddenly understand how violently players utilise that 3rd dimension. Glorious rainbow and banana shaped ball flights and winners raining down on court are the norm these days, and the Magnus Effect, partially facilitating Rafa and his contemporaries high margin offence and defence, gets some of the credit.

Medvedev, and his flat-as-a-pancake buddies, simply don’t get to use as much of this modern flair.

Bounce

But the trajectory factor isn't the only difference for flatter hitters on clay relative to the quicker surfaces. The impact of their ball when it lands also doesn't have the same bounce characteristics on a clay court as it would on faster grass or hard, thanks to greater friction, different restitution, and bounce height with loose, softer particles on the red stuff. This, unlike the trajectory issue above, affects both the serve and groundstrokes.

As @FogMount puts it:

The flat shots, landing in the same place in the court at a lower angle of 11.9°, continue sliding throughout the bounce on every surface. This means they’re slowed by friction over a more extended time span, and they show bigger variations in speed.

On a quick hard or grass court, Medvedev et al’s flatter shots slide through the bounce but leave the surface relatively quickly, taking time away from the opponent and staying low. But while a heavy topspin shot retains much of its speed across all surfaces by the time it reaches the baseline (although bounce height will differ), a flat shot loses a more significant chunk of its baseline speed on slow clay compared to faster grass and hard courts thanks to the differences in surface composition (it will also bounce higher). This is due to the angle the ball hits the ground at, and the restitution (ie the resumption of the ball's original shape through elastic recoil) during and after the bounce. A heavy topspin ball quickly starts rolling again rather than sliding after the bounce, due to the spin and a greater vertical speed when hitting the ground. A flat shot slides through the bounce for longer due to no or less spin and a lower vertical speed (and higher horizontal speed) when hitting the ground, which on clay means more time spent losing energy due to the friction and softness of the loose surface.

Rod Cross notes:

Courts that are slow at low angles of incidence are not necessarily slow at high angles of incidence.

Put simply, just because a flatter hitter’s strokes are slowing on clay, doesn’t mean heavy topspin hitters are suffering from the same fate on that surface.

Therefore the same penetrating flat strokes, that have seen Medvedev dominate many recent hard court tournaments, don’t count for quite the the same level of weaponry on the clay. Not only do the flatter hitters have to navigate less forgiving trajectories through the air, but even upon hitting the ground some of their usual effectiveness is blunted. A double whammy of disadvantageous dynamics.

Exceptions?

Medvedev is actually a very interesting example because he manages to hit flat from extremely deep positions on hard courts, perhaps more consistently than anyone I’ve ever seen. He’s quite a good counter argument to the trajectory disadvantage. But he mitigates this handicap thanks to the following:

How penetrating his shots are when bouncing on quicker surfaces, therefore causing his opponents more of a problem, as noted above.

His height at 6ft 6+ (the higher the contact point, the safer the trajectory, as below):

There are of course exceptions to all the above. For e.g Cristian Garin, who is a great clay courter, hits relatively flat. And Andreas Seppi is better on clay than he is on hard courts (although his best surface is grass which does fit the narrative). There are also a multitude of additional factors and variables during competitive matchplay that can render spin rate as a sometimes unimportant factor. Medvedev beating Tsitsipas and Djokovic (two excellent clay courters) on the way to the Monte Carlo semi-finals in 2019 is a good example of the much bigger picture at play.

However the point remains that being able to hit high margin (ie safe and high net clearance) offence and defence is a consistently vital part of modern tennis, especially on clay. Nadal, Thiem & Casper Ruud conveniently happen to be the three most extreme spin opposites to the ‘flat’ section of the spin rate plot…

…and absolutely no prizes for guessing what all three of them count as their favourite surface.

Spin is certainly not the be-all and end-all of clay performance. But it undeniably lets the very best clay courters do things that Medvedev and his fellow pancake boys probably wish they could, when playing on the red stuff.

Coarse and irritating indeed.

— MW

If you’d like to get issues like this, and match analysis for every big final, you can subscribe here. There’s only about 24 hours left to sign up as an early adopter and get a discounted membership:

See you on Sunday for the Monte Carlo final.

Twitter @MattRacquet

p.s If you’d like to see a real world example of the spin vs flat dynamic play out, Tsitsipas — who hits with a lot of margin, a lot of spin on both wings, and is an excellent clay courter — easily beating Aslan Karatsev — who has an extremely flat backhand — happened in Monte Carlo on Tuesday, and is worth watching (highlights). Here’s a quick clip to demonstrate the different flight path of their backhands:

p.s 2: I will do something similar for the women’s tour soon. Given the differences in technique between the two tours it needs its own piece.

// Looking for more?

Monte Carlo Final Analysis - Tsitsipas vs Rublev: https://theracquet.substack.com/p/monte-carlo-final-tsitsipas-vs-rublev

The Modernisation Of Tennis: https://theracquet.substack.com/p/the-modernisation-of-tennis

Federer, Nadal & Djoković Rivalry Impact: https://theracquet.substack.com/p/federer-nadal-and-djokovic-make-a

Tennis Pontificates About Format Changes Again: https://theracquet.substack.com/p/here-we-go-again

Tennis’ Identity Crisis: The Umpire Problem https://theracquet.substack.com/p/tennis-identity-crisis

Analysis of the Djoković Medvedev Australian Open Final: https://theracquet.substack.com/p/the-racquet-micro-not-macro-match

Analysis of the Nadal Medvedev US Open Final Final: https://theracquet.substack.com/p/the-racquet-the-5th-set

I meant to comment earlier but thoughts on Davydenko/Meddy. At his best on hard like Meddy but improved on clay and had done great results. I watched a few of his clay highlights ( Monte Carlo, RG) recently thinking about this. Right up on baseline, cutting off spin angles with his quick feet and whippy swings. I do find Meddy is too far back ( bigger swing?). Can he adapt? Take it earlier? Reduce the swing? No one talks about Davydenko anymore but as a flatter hitter against more spinny balls he had huge success. Thoughts?

You tweeted this out which is fascinating:

http://on-the-t.com/2021/04/17/Return-Impact-H2H/

I noticed that there is a set of young players - Tsitsipas, Auger-Aliassime, Mussetti, Thiem - who move back on a substantial amount of their second serve returns, be interesting to hear your thoughts on that.

I put everyone in opposite Djokovic since I figured you might as well compare them to best returned. Happy to see one of my fave youngsters, Jannik Sinner, has almost identical return position including, like Djokovic, very little variation in position.

Also interesting that while Federer (unsurprising) and Murray (a little surprising) have more aggressive return positions than Djokovic, the only youngster I put in with a more aggressive position was de Minaur (and he varies more, sometimes less aggressive on second sometimes more).

Be good if someone put a number on distance from baseline on the four return positions so one could quickly scan everyone's relative aggression though the graphics are fantastic for seeing the variation.